A community stake in geological disposal

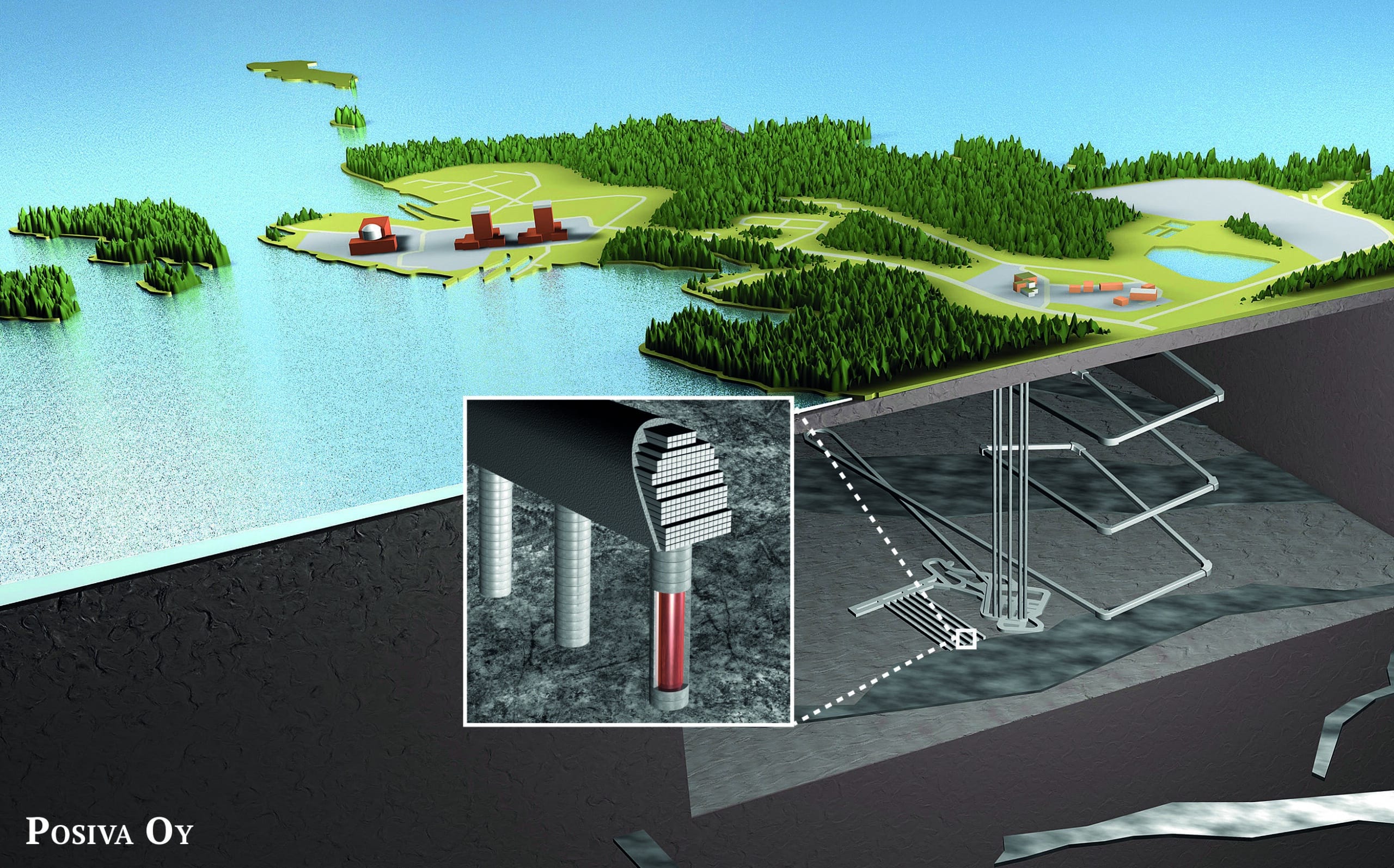

In Finland, the construction license for the Posiva – ONKALO – deep geological repository was granted in 2015. The site was selected after a long process, beginning in 1983.

For over 40 years, UK Governments have failed to secure a site for an underground radwaste repository. Phil Davies* has a proposal…

A national screening exercise is under way, precursor to new discussions with communities about their geological potential to host a national Geological Disposal Facility (GDF). The Society has established an independent panel to review and evaluate the guidance for national screening.

Solution

A disposal solution needs to be found. While there are opportunities for re-use or conversion of some stockpiled nuclear materials, there is no further use for the majority of the UK waste inventory. Safe, monitored storage of waste is an interim solution, but it isn’t sustainable for thousands of years. Nor is such an approach used for other long-term hazardous wastes.

Potential negative impacts will concern members of any community where it is suggested that a GDF might be sited, such as the safety of transporting waste consignments and risk of ‘blight’ on image and property values. In addition to facing these issues, and most importantly, the aspiring developer will need to satisfy the public that radionuclides that will eventually leak away from the repository will not harm future generations. Experience shows that a hybrid storage/disposal design may be somewhat more acceptable to the public, the waste remaining retrievable ‘just in case’.

Host

In current thinking, volunteer host communities will be sought, and presumably communities that appear to be located in feasible GDF locations will be approached. As soon as a location is mentioned, expressions of local concern and opposition will follow. The would-be GDF developer will be cast as the party looking to bring bounty, or detriment – probably both. Local politicians will be in a difficult position – various electors will take a negative view of whatever position they adopt. The seeds are thus sown for yet another failed siting initiative.

Alternatively, we could try to avoid the predictable ‘rejection and retreat’ scenario. What if the project itself were partly ‘owned by’ a community, not something ‘done to’ a community? A special-purpose community stake company could obtain its own independent advice on the feasibility and safety of hosting a GDF. Such a company would be hard-wired to one or more local authorities, thus providing excellent public transparency and accountability.

Dividend

If feasibility and safety studies showed sufficient promise, and political agreement was achieved, the company would continue as a developer partner for subsequent steps. This would allow continuous public scrutiny of feasibility and safety ‘from inside the tent’. The company would earn dividend through its evolving engagement in the project, this arrangement supplanting the ‘negotiated benefits’ model. The dividend income (which would continue right through to facility operation) would be available for local socio-economic investment.

Moving beyond the traditional us-and-them, developer versus community approach, this concept could be applied to other projects where public trust or lack of it is a significant issue… fracking, anyone?

Further reading

- History of nuclear waste disposal proposals in Britain

- Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, update 13 April 2017

- Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, annual report published 8 December 2016

* Phil Davies is a freelance consultant with Westlakes Nuclear Limited. E:

This article first appeared in the October 2017 edition of Geoscientist, the magazine of the Geological Society of London.

Share this article

Related articles

Help us grow and achieve your potential at a values-driven business.